Appendix A: How to Do This and Why

by Leonard Richardson

Like the best science, Thoughtcrime Experiments was born of hubris and a desire to show them all. As a writer, I was aggravated at the existing SF markets, for the usual writer’s reasons. As a reader, I appreciate that markets exist to separate the good stuff from the bad, but a market runs on the taste of its editors. Sumana and I felt that our tastes weren’t being represented.

In December of 2008 I began to daydream about an ideal market for short speculative fiction. It would pay reasonable rates, it would publish online to reduce overhead, it would liberate stories with a Creative Commons license that allowed for derivative works. Most of all, it would publish only stories that I thought were great. I realized that 1) there was no reason I couldn’t do this, and 2) even in my daydream I was implicitly the one doing it, because how else is the editor supposed to know what I think is great?

Old science fiction sometimes handwaves society’s problems away to get to the plot. “Everyone realizes” that pollution is kiling the planet or “everyone decides” to move to Social Credit. In real life this strategy will not solve society’s collective action problems, but when there are only one or two people involved, it works great. I told Sumana about the plan, and she liked it, and we did it.

This appendix shows how we did it. It was not difficult but it did take a lot of time spread over four months. I write this appendix in the spirit of the old Whole Earth Catalog, in the hopes of inspiring other people to put in some time and money and produce their own anthologies of the fiction that tickles their fancy. We also hope that we have interesting data to present about the state of the market.

The Gathering

I initially described this idea as a “one-shot webzine”. Sumana pointed out that such things are called “anthologies”. We were making an anthology!

The first step was to put up a web page with a teaser cover and submission guidelines. We registered a Gmail account and told prospective authors to send their stories to the Gmail address. We said that we preferred plain text, but that any format was fine.

We offered 200 USD for first electronic rights and the rights to distribute a story under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Sharealike license. We asked for no reprints or simultaneous submissions. We promised a kill fee of $75 in case we bought a story and for whatever reason weren’t able to deliver the anthology. We said that we prefered stories that had been rejected multiple times; this was to test the oversupply hypothesis (see below).

Announcing the anthology

After putting up the web page with the guidelines we announced the anthology to online market lists and other places authors find out about anthologies. Over the time we were open to submissions, we sent out about forty announcements to writing groups and market lists.

The two most useful market lists are Ralan’s Webstravaganza (www.ralan.com) and the specficmarkets community on LiveJournal (community.livejournal.com/specficmarkets/). When we submitted to one of these market lists, we got a surge in submissions the next day. You should announce your anthology in these two places and also on Duotrope’s Digest (duotrope.com).

We wanted to get racial and gender diversity among the submitters (and, hopefully, the final authors). So Sumana searched for writers' groups for women and people of color, and sent them emails requesting submissions.

The original closing date for submissions was March 31st, “or until full”. On February 1st, looking at the entries we’d received, we moved the deadline forward to February 15th. We originally intended to publish five stories. If you offer the rates we offer, you announce in the places we announced, and you’re serious about only publishing five stories, I estimate you should keep submissions open for one month.

We changed the deadline on our site, and notified Ralan and similar sites, but some places (like SFWA) had publicized our initial request for submissions in paper or email newsletters, and didn’t update their readers when we changed the deadline. So we got a few straggler submissions in late February and March. Sumana told them we’d filled the anthology and they reacted okay.

The Submissions

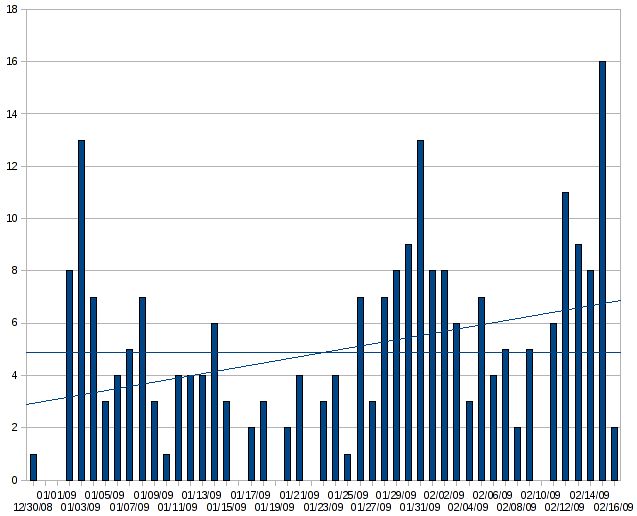

We received 241 submissions between December 31, 2008 and February 16, 2009. Here’s the graph of submissions over time. The mean submissions per day was 5.0 in January and 6.7 in February.

The spike right after January 1st came from ralan.com and the spike at the end of January came from specficmarkets. Of course, the busiest day was the last day we were open for submissions.

As stories came in, we read them. At first both Sumana and I read slush, but after it turned out we were duplicating effort, I stopped and Sumana took over. Here’s Sumana’s description of this process:

“To get a batch of stories I went into the Thoughtcrime Experiments Gmail account, downloaded all the stories that we hadn’t yet read, and tagged that email with the ‘unread’ tag. These went into a folder called ‘to-read’. Most of the stories were plain text, RTF, or Microsoft Word documents, so I could read and annotate them in TextEdit, a lightweight editor application on my Mac. Others were PDFs or OpenOffice documents, which I could also read fine. Only twice did I have to write back to an author and request another file format.

“I was doing a lot of traveling at the time, and with the stories on my laptop, I could read slush on the road, without needing a net connection. Sometimes a quick skim gave me enough data to reject a story, but I read most stories all the way through. Sometimes I added some notes in italics at the top of the story file about what I especially liked or had problems with.

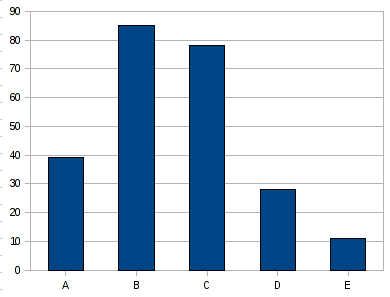

“When I finished, I classified the story into one of five quality tiers. From A to E the tiers were ‘God no,’ ‘no,’ ‘maybe,’ ‘pretty good,’ and ‘Oh my God we have to publish this WOW.’ I put each story file into the A, B, C, D, or E subfolder of the ‘read-already’ folder on my hard drive.

“Once I had a net connection again, I went through my folders and opened up the Gmail account, looking at emails tagged with ‘unread’. I tagged the initial submission email with a Gmail tag indicating what tier the story fell into.”

In retrospect, we only needed three tiers (“no”, “yes”, “yes!”). But we didn’t know how many good stories we would get! We thought we might have to make fine distinctions between “okay” and “pretty good.” And having five tiers made it possible to give you this cool-looking graph of how much we liked the incoming stories:

After tagging a story, Sumana either rejected it or flagged it for my attention. When she flagged a story, she also started a draft email telling me what she liked and didn’t like about the story. This draft email was never sent, though its contents often became feedback that was sent. It was just a convenient way of attaching a conversation to a message in Gmail.

I read all the stories in tiers D and E, and some of the tier C stories. We discussed the stories by appending back-and-forth comments in the Gmail draft associated with the original submission email. We used “for Leonard” and “for Sumana” tags to send the “message” back and forth. We also had face-to-face conversations about the stories, which became more frequent and intense as we rejected better and better stories.

In this way, once the deadline had passed, we converged on a small set of twenty-four stories that we had a positive desire to publish—not “I could see this in a magazine” or “this could be great with some work” but “let’s publish this.”

We tweaked the submission guidelines over time to affect the mix of stories we received. The main problem had to do with the title “Thoughtcrime Experiments”. To me, the phrase has a playfully sardonic, Dr. Strangelove sensibility. Many writers saw it quite differently. Mark Onspaugh (“Welcome to the Federation”) commented: “The title... seemed very dark and somber.” We received many depressing stories of Orwellian dystopias and forbidden medical experiments. I now see why so many magazines nowadays explicitly request stories with a light tone, or at least not stories that are fricking depressing. I did the same, changing the guidelines near the end of January to ask for stories with a light tone. This seems to have worked.

I also added to the guidelines that I wanted to see more stories with space aliens, because space aliens are awesome. However, only two of the stories we’re publishing include space aliens. By contrast, there are four fantasy stories in here (five, if you count “Single-Bit Error”), even though in the guidelines I said “it’s not as likely I’ll pay $200 for a fantasy story.” Go figure.

Although the guidelines said we were open to horror stories, in reality only one horror story got as far as tier C. It turns out we don’t like horror.

Sending rejections

Sumana spent a lot of time—sixty to eighty hours—writing personalized rejection notices. Honestly, that’s about ten times as much time as I would have spent. She got a lot of appreciation from authors for her trouble, and, when we requested them, many repeat submissions. Thirty people sent in more than one submission. Many second, third or fourth submissions made it to the final stage, but six of the stories in this anthology are the first and only story the author sent us. Only two were second submissions. (One author sent us two stories and we chose the first one.)

One useful side effect of this work is that I no longer take rejection notices at all personally.

Sumana describes the rejection process:

“I sent immediate rejections to stories in the bottom two tiers, and deleted those files from my laptop. After about a month of reading, we’d accumulated enough stuff in the top two tiers that Leonard and I decided to reject all the stories in the middle tier.

“When we received a story in the top two tiers, I sent a reply ASAP indicating that we had received the story, enjoyed it, and were putting it under strong consideration.” [This was to stop the aggravating guessing game of “are they really considering my story or have they not gotten to it yet?’, which I dislike as a writer. -LR]

“When rejecting stories in the top three tiers, I sent a message saying ‘this didn’t quite make it, but do you have anything else?’ This was how we got multiple submissions.

“Rejection is touchy. Since I had the time, I tried to personalize rejections, always telling the author something I liked about the story, or explaining that we, for example, weren’t really into horror.

“Even personalized notes contain a lot of boilerplate. I recommend the ‘Canned responses’ feature of Gmail, currently available from the “Labs’ tab in the Gmail settings configuration. Here’s one base for a rejection letter:”

Thanks for submitting your story to Thoughtcrime Experiments. Though it is a strong piece, I’m sorry to say we’ve decided not to buy it. Best wishes for your future writing projects, though.

Regrets,

Sumana Harihareswara

Editor

Thoughtcrime Experiments

“In many rejections I said that, if the author asked, I could provide suggestions for improvement. About forty took me up on it, so (mostly after we’d chosen the finalists) I spent about forty hours writing critiques of rejected stories. Several authors were very grateful. In a few cases, I took a chance and gave some criticism in the initial rejection letter (like, ‘the plot needs a better payoff’).

“Either because we were a tiny fish in the pond, or because only net-savvy authors found us and wrote to us, or because I tried to be nice, I got only 1 jerky reply to a rejection.

“For about 10 stories, we asked the authors to consider revisions. Leonard and I discussed our suggestions for revision before emailing or telephoning the authors, and we gave a deadline for revisions that was a little past the regular submission deadline. Some of those stories made it into the anthology and some didn’t, but the authors seemed glad to discuss them with us even if we ultimately rejected the stories. In one or two cases miscommunication or a tardy reply meant that time ran out on our deadlines before the author could make a revision that she wanted to submit, but I think there were no hard feelings.”

Culling the Herd

Okay, so we got it down to twenty-four stories that we really liked. Now we had to get it down to five. Our first way of dealing with this was to increase the number of stories we planned to publish. We brought it up to the present nine. We thought that more than about ten stories would overwhelm today’s flitting, web-based readers. With nine stories we could publish more of what we liked, while staying in single digits.

Up to this point the decisions were pretty easy. The only stories we’d had any difficulty rejecting were ones that were extremely well-written but flawed in a way the author couldn’t promise to fix. But now we had to reject stories we loved and could have published. Sumana says: “I cried a little bit rejecting a story whose author had worked with us to edit and improve it.”

Rather than gradually whittling away twenty-four to get to nine, we switched to the opposite approach. We wrote tables of contents trying to find sets of stories that worked well as a group. We tried to balance serious and funny stories, stories by women and by men, and (apparently) fantasy and science fiction stories.

Artwork

Unlike the stories, the artwork for this anthology was commissioned. We emailed artists we knew or that were recommended by friends, and offered $100 for a full-page black-and-white illustration.Although we approached many artists whose work we’ve enjoyed, we only got good results from artists with an explicit commission policy. Other people we contacted were too busy or never wrote back. The exceptions are Patrick Farley, who doesn’t have a commission policy but who we know personally; and Ruben Bolling, who responded to our unsolicited email, but whose price for a full-page illustration we couldn’t meet.

We briefly considered asking the artists to illustrate the stories, but rejected this idea because it would have drastically slowed down the anthology. We would have had to commission the art after choosing which stories to publish. Instead, we basically told each artist to draw something awesome.

This was probably too general a rule. Although each individual illustration is great, taken together they don’t have the same variety as the stories we picked for the anthology. If we do another anthology, we’ll work with the artists to ensure more variety. But giving the artists free rein meant that the art was ready before we’d chosen which stories to publish.

We also commissioned the five pieces of art before deciding to publish more than five stories. We'd like this anthology better if there was more art.

After Choosing

Once the stories were chosen we thought we were almost done, but it wasn’t even close. First, we ran through this checklist for each story:

- I sent out the contracts via email, asking for two signed copies via mail: one for me to keep, one to countersign and send back. I also asked for a short bio and list of publications. (I actually did this later, which was a sign that I wasn’t thinking ahead. There’s no reason not to do this up front.) See Appendix B for the contract we used.

- As the contracts came in, I counter-signed and sent them back. (I also offered to do an informal contract over email instead of a paper contract, which three authors prefered.) I then paid the authors via PayPal.

- Most of the stories needed revisions. Only three needed significant revisions. Once any revisions were done I did a line edit, using the OpenOffice Writer equivalent of Word’s “Track Changes” feature. One story was submitted in plain text, and I sent revisions as a diff.

- Sumana and I wrote introductions for each story, and edited the author bios.

Then it was time for one final push. I converted the revised stories to HTML and wrote a stylesheet for the anthology. I tried a number of ways of doing this. I ended up saving them as HTML from OpenOffice Writer and then using regular expressions to simplify the HTML and replace non-ASCII characters with HTML entities.

It was tempting to save the files as Docbook files, which are very easy to convert to HTML, but I don’t recommend it. OpenOffice’s Docbook conversion stripped italics and other emphasis markers from the stories.

At this point, the nine HTML files became the master copies of the stories.

I put the HTML files online, along with the introductions and bios, and gave the authors one more chance to spot errors. I chose pull quotes for the stories: three pull quotes for the really long stories, two pull quotes for the others.

Sumana wrote the introduction, and I wrote (most of) this appendix.

Once the authors had a chance to look at their stories (finding many more errors), it was time to lay out the PDF and print-on-demand versions of the anthology. We futzed around with desktop publishing programs for a while, and then I decided they were a waste of time. I’d already done the layout with CSS, and OpenOffice Writer could import the HTML files with the layout intact. I had to spend a couple of hours tweaking things, but it was less time than we’d already spent trying to learn desktop publishing.

Budget

We paid $200 for a story and $100 for a piece of art. Thanks to print-on-demand and do-it-yourself, that was our entire monetary expense. For the record, here’s the math:

Stories: $1800

Art: $500

Total: $2300

Our friend Rachel Chalmers put up $200 to sponsor a story, so our out-of-pocket expenditure was only $2100. That’s an amount we can afford to spend on a big multi-month hobby project, but it’s not a trivial sum for us. And most of the stories in this anthology didn’t even get paid a pro rate! $200 is the SFWA pro rate for a story of 4000 words; only “Daisy”, “Goldenseed” and “Qubit Slip” are under that threshold. If we’d paid five cents a word for all the stories in this anthology, the stories alone would have cost $2435!

You can see why most markets don’t pay very well. If we’d paid $50 for stories and $20 for art, this anthology would have cost $550, a much more manageable sum, and one we possibly could have recouped by selling copies of the anthology. Would we have gotten as many good submissions? Probably not. But if you’d like to run a lower-budget version of our experiment, it would be great to see what happens.

Our time investment was considerable. Some very rough estimates:

- 200-300 person-hours responding to stories that were ultimately rejected

- 20 person-hours talking to artists

- 25 person-hours doing contracts, revisions and line edits

- 40 person-hours doing layout, website design, and POD setup.

That’s not counting time spent doing promotion, which will happen after this essay is written.

The oversupply hypothesis

Even if you don’t like all the stories in Thoughtcrime Experiments, I hope you’ll agree that they’re of similar quality to the stories you see in big-name print magazines. The “experiment” behind Thoughtcrime Experiments was to verify the existence of such stories floating around in editors’ slush piles. To get a firsthand look it was necessary to become editors.

If you listen to editors complain about unsolicited submissions, you’ll get the impression that pretty much everything that comes into the slush pile is terrible. That simply writing a grammatical story with a plot puts you in the upper half of the slush pile.

This makes beginning writers feel good, and in fact our experience shows the upper-half thing to be true, but it’s an illusion. A story that’s better than 80% of the slush gets rejected. You can’t shoot for the upper half of the slush pile, you have to shoot for the top five percent.

Of the 241 stories we received, we put thirty-nine into tiers D or E. That’s 16%. Only one of every fifteen stories we got made us think “it would be cool to publish this” for any length of time. And we were able to reject fifteen of those thirty-nine stories without really hurting. We were left with twenty-four stories, or 10%. Remember Sturgeon’s Law: “Ninety percent of everything is crap.”

From that 10% we could have made three anthologies. We ended up publishing nine stories, or about 4% of the total. It’s true that we got some really bad stories, but we also got a lot of great stories. And almost all of the stories we published had been rejected from somewhere else.

I asked the authors we’re publishing for details on their stories’ previous rejections. All in all, nineteen markets rejected one or more of these stories. The mean number of rejections was 3.1. Asimov’s rejected four of these stories—almost half. F&SF and Strange Horizons each rejected three. One Story and Weird Tales each rejected two of them.

- No prior rejections: 2 stories

- 1 prior rejection: 2 stories

- 2 prior rejections: 1 story

- 4 prior rejections: 2 stories

- 7 prior rejections: 1 stories

- 9 prior rejections: 1 story

Is there something wrong with these markets that they passed up on these gems? Absolutely not. We got fifteen other stories of similar quality, stories with (one assumes) similar backstories of rejection, and we rejected them. There’s too much bad stuff in the slush pile, but there’s also too much good stuff.

Every story needs an editor to champion it. One thing we conclude from this experiment is that there aren’t enough editors. We were able to temporarily become editors and scoop a lot of great stories out of the slush pile.

It’s not like we were these stories’ only hope. At least one of the stories we rejected was published in a different market before this anthology came out, and at least one has been bought by another market. These stories were in someone else’s top five percent. But a lot of the stories we’re publishing had been rejected by the markets I read regularly. Even if they were published, I probably never would have read them.

It’s well known that there’s an oversupply of stories relative to readers. That’s why rates are so low. Our experiment shows that there’s an oversupply of stories relative to editors. By picking up this anthology you’ve done what you can to change the balance of readers to stories. I wrote this appendix to show that you’ve also got the power to change the balance of editors to stories.